Georgette Heyer took pride in her a long, successful, and generally happy marriage. If, as her biographer hints, its early years were filled with financial stress, and in later years may have included a discreet affair or two on her husband’s side, they shared a strong partnership, and in later years were united in their pride and love for their only son, who followed in his father’s footsteps as a barrister.

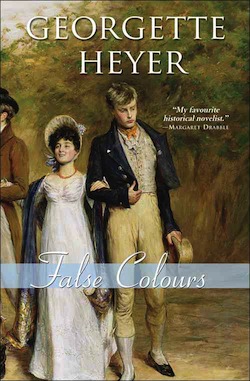

But for all her own domestic happiness, Heyer witnessed multiple disastrous marriages, and in False Colours, takes the time to explore the long term effects of unwise pairings on children and even more distant relations.

As the novel opens, Kit Fancot has returned home from a diplomatic posting unexpectedly early out of a vague feeling that something has happened to his identical twin, Evelyn. Sidenote: And this rather answers the question of whether any of Heyer’s protagonists ever got involved in politics. Kit’s job in the diplomatic corps is about as political as jobs can get, and it’s a job gained from political connections. Having said that, this is yet another case where the political job happens outside of Britain—as if Heyer was determined to keep politics outside of London, even while occasionally acknowledging its existence there.

His mother, the generally delightful Lady Denville (do not, I beg you, call her a dowager), confirms Kit’s fears, saying that no one has heard from Evelyn for days. Not exactly unusual, but Evelyn is supposed to be going to a dinner party to meet his possible future fiancée to get the full approval of her family before the betrothal becomes official. If he doesn’t show up, not only will the girl, Cressy, be publicly humiliated, but the wedding will be off. And that in turn will jeopardize Evelyn’s chances to take control of his own estates—and finally have a purpose in life.

Not to mention another problem: Lady Denville, is deeply in debt. How deeply she doesn’t know, but the novel later reveals that her debts total at least 20,000 pounds—in other words, two years of income for the fabulously wealthy Mr. Darcy, or the equivalent of millions today. And that’s not counting the full dressmaking bills or the jewelry bills. Adding to the issue: Lady Denville, while gambling, staked a brooch with the claim that it was worth 500 pounds—forgetting in her excitement that the brooch was actually just a nearly worthless replica. She sees nothing wrong with this; her sons are both horrified and amused. Lady Denville’s few attempts to practice Economy have gone very badly indeed; her later arrival at the ancestral estate loaded down with items that none of the residents can use (as the horrified housekeeper notes, the Spermaceti Oil is quality stuff, certainly, but they don’t even use lamps) shows that she is in the grip of a shopping/gambling mania.

Lady Denville is loosely inspired by Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, who reputedly had the same winning charm; the text notes the resemblance of the two. Like Georgiana, Lady Denville gets away with this sort of thing partly because she is known to be a member of a very wealthy family—as another character later grimly notes, the jewelers are well aware that the family will eventually pay for all of the jewelry she’s paid for without hesitation to save the family reputation and ensure that they don’t end up getting dragged through courts. She is also delightfully charming and an excellent hostess, adored by her sons and her goddaughter and even tolerated by the not-so-tolerant.

But the major reason Lady Denville is forgiven is the general awareness of the bleakness of her marriage. At a young age, she married a considerably older man charmed by her beauty; the two, alas, had absolutely nothing else in common. Exasperated by her even then spendthrift nature, her husband became more and more emotionally and verbally abusive. She in turn increased the spending and the flirtation (the text suggests infidelities on both sides) and devoted herself to her sons. This in turn created a strong rift between the twins and their father. The result: the father is convinced that Evelyn will be as irresponsible as his mother, and therefore ties up the estate preventing Evelyn from gaining control of it until he is thirty—or has convinced an uncle that he is socially and fiscally responsible. But with nothing to do, and a decent income from his principal, Evelyn becomes socially and fiscally irresponsible, increasing the family strain. The stress helps encourage his mother to take more spending sprees.

Interestingly enough, from the text, it appears that Lady Denville and her husband married after having the exact sort of courtship Heyer celebrated in her earlier novels—particularly Faro’s Daughter and The Grand Sophy: brief and superficial, with a couple who seemingly have little in common. It was a situation that Heyer could and did play for comedy, to excellent effect, but perhaps years of writing such scenes had caused her to wonder what would happen next. The answer was not entirely happy.

Cressy, meanwhile, is dealing with her own father’s recent marriage to a woman she dislikes, a marriage that has put her in a very difficult position at home—so difficult that she is willing to enter a marriage of convenience with Evelyn just to get away from home. The text hints that her own parents did not exactly have a happy marriage either. Here, Heyer reassures readers that an unhappy marriage does not necessarily need to result in childhood unhappiness: Cressy, like Kit, is self-assured and content until her father remarries. Evelyn, however, is another story.

For extremely overcomplicated reasons that don’t really make sense the more you think about them, so don’t, Kit agrees to pretend to be his twin brother for a bit—not realizing that this pretense will make it very difficult for him to search for Evelyn and ensure that his twin is ok. The masquerade creates other social difficulties as well: Kit hasn’t lived in London for years, and doesn’t know Evelyn’s friends. And although the twins look alike their personalities are very distinct. Kit and his mother soon realize that to continue to pull off the deception, Kit needs to head to the country—a great idea that runs into some problems as soon as Cressy’s grandmother decides that she and Cressy should join Kit there.

The ending of the book feels more than a bit forced—no matter how many times I read this, I can’t see Cressy marrying Kit instead of Evelyn as all that big of a scandal: they are twins. Just say that the newspaper and their friends got things mixed up. It happens. Compared to the other, real scandals Heyer has detailed in previous books, this is nothing. Nor can I see Evelyn’s issues as all that terrible, or the issue of his mother’s debts all that urgent given that the text has also told us that her creditors know the money will be there eventually and are willing to wait for it. But I do enjoy the novel’s quiet exploration of marriages arranged for love, infatuation, or convenience, and the discussion of which is best. And that—in a novel discussing the issues with romance—Heyer for once delivers a convincing romantic couple. Their obstacles may be—ok, are—ludicrous and unbelievable, but their hopes for future happiness aren’t.

False Colours is a quieter book than many of the previous Heyer novels, marking the beginning of her more thoughtful and less farcical looks at the Regency world she had created: a world where young women often did marry older men that they did not know well, where the older men found themselves paying for their wives’ reckless spending and gambling. It was a theme she would return to as she continued to explore the cracks in the farcical, escapist world she had created.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.